Augusta Sparks Farnum is Going. Are You Coming?

When I first moved to Walla Walla thirteen years ago, I thought I would never find a way into the landscape. We arrived, by plane, in August. Looking out the window as we flew from Seattle east across Washington state, it was easy to see the world changing: snow covered mountains, green sloping hills, then brown with the occasional circle of irrigation green. There were fires in the mountains that August, as there are almost every August now, and when we arrived at our new house, there was a dusting of ash on the porch.

I came to Walla Walla from the green east coast. August in New Jersey, where I grew up, was thick. The trees ticked with insect life. The late summer heat pressed heavy at night. I remember lying in bed as a kid waiting for a storm to break, for rain to finally come and cool things down. You could feel the water in the air well before it made itself visible. In Walla Walla, even in the hundred plus, glaring-sun days of August, the nights are cool and dry. There’s little tree cover. You look up at night and you can see stars stretching forever.

During childhood, it felt, always, as if the natural world was filled with magic. In Harriman State Park, half an hour from where I grew up, there were caves that had sheltered bandits during Colonial times. We hiked there once on a school field trip, and the caves, narrow and barely large enough to cover a class of children when the rain came, seemed like Ali Baba’s cave to me, ready to open and draw us all inside if we could just find the right words to say. Closer to home, in the woods stretching out from the back of my friend’s house, was a rock so enormous it could hold fifteen kids. It felt like a ship in the middle of the forest, despite our being miles and miles from the sea. There were stories everywhere—in the roots of trees elbowing up from the earth, in the white flowers that edged our backyard like so many bridal bouquets lined up together, in the old stone houses positioned so close to busy roads that you were forced to remember that, once upon a time, the roads had been paths, and the houses had been built in what seemed would forever be isolation.

But here in Eastern Washington? Just dry brown earth and wheat fields rolling and rolling and rolling, golden everywhere, no real green in sight. The sun was so bright that there seemed no place for mystery to take shelter.

It took me years of looking to find a place to rest my imagination here in Walla Walla.

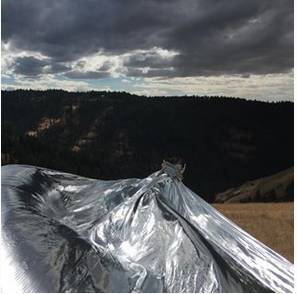

And then I saw this photograph, by Augusta Sparks Farnum: an apple orchard heavy with fruit, the apples as bright as any that Snow White might have pressed to her lips; the sky above, relentless in its perfect, frozen blue; the thick darkness beneath the sagging boughs; and through it all, like a road, like a river, like the sky itself above, a path of Mylar. There’s an extraordinary stillness here, but once you start looking, the stillness vibrates. Something is caught in that reflective material, and whatever it is that’s caught changes the material even as you look at it. The path, at first a narrow reflection of the sky, billows quietly, and then not so quietly—it gets louder and louder and louder until the only thing holding it from pulling away is that fallen apple pressing it back to earth. And then I look at it again, and the Mylar is no longer a river or a road or a scream; it’s become a dress, something to clothe oneself in that reflects the entire world.

Farnum found the orchard lined through with Mylar while driving around the valley’s back roads. Apple farmers use it to reflect the sun onto the underside of fruit in order to speed up ripening. The material is thin, and gathers up small, and can roll out for the entire length of an orchard. It interferes with life and also pushes the processes of life to move faster. It’s so light that, if its not tacked down, even a small breath of wind will move it.

The Mylar goes with Farnum now where she goes.

It spins out into the air above fields just starting to push their shoots above the earth.

It hisses into fields already gold.

It repositions clouds gathering in the sky so that they gather on the earth, and it screams back at the sky that the clouds down here are just as intense and overwhelming as anything the sky can offer.

It interferes with the natural world and responds to the natural world, and it is shaped both by the wind and by Farnum’s eye. I could stare at any one of these images for hours. They vibrate for me in the tension between their stillness and their movement, in the way they embrace rage and strength and grief and joy. They make me re-see the landscape here, pull me into it, but also push me out.

They make me feel like I’ve come back around to the child I was so long ago who could see a ship in the forest or a fairy house in the roots of a tree; but that whatever it was that allowed me to see those things then is coupled now with the power and experience of age.

I’d love to hear on my Facebook page about what kinds of stories you see in these photographs. For me they hold fairy tales, the kind of fairy tales that stress the power of the unknown and that don’t have any interest in shying away from danger—the kind of fairy tales I hope one day to write myself.

All images copyright Augusta Sparks Farnum