On First Sentences

I’m getting ready to give a talk at the Walla Walla Public Library about Charlotte’s Web this Wednesday. (And please, unseasonable snowstorm predicted for next week, hold off at least until Thursday!) The talk is going to focus on reading like a writer: that is, reading E. B. White’s novel to figure out how it’s made. This is something that I think a lot of writers do when they come across a piece of writing that they’re blown away by. They try to figure out what tricks the writer used in its construction that make it work so well.

White has a lot of tricks up his sleeve. He’s got simple prose that, really, is not so simple after all: every word is placed with intention to build rhythm, to create atmosphere, to assert that extra stuff is unnecessary. He’s got a trust in lists as a kind of supporting architecture; the lists (mostly of food, but also of garbage, and tools, and other farm-related things) work to create a structural integrity so that the novel coheres beyond plot. He’s got an intense focus on rhythm: certainly in his sentences, but also in larger strokes--chapters whose primary work is to slow down the plot and give the sense of passing time; chapters whose primary work is to delay action in order to build tension. He’s got his roving point of view, whereby he moves in and out of characters’ heads, so that the book moves from centering on Fern to centering on Wilbur without our even noticing the moment where the focus changes. And he’s got that killer first sentence:

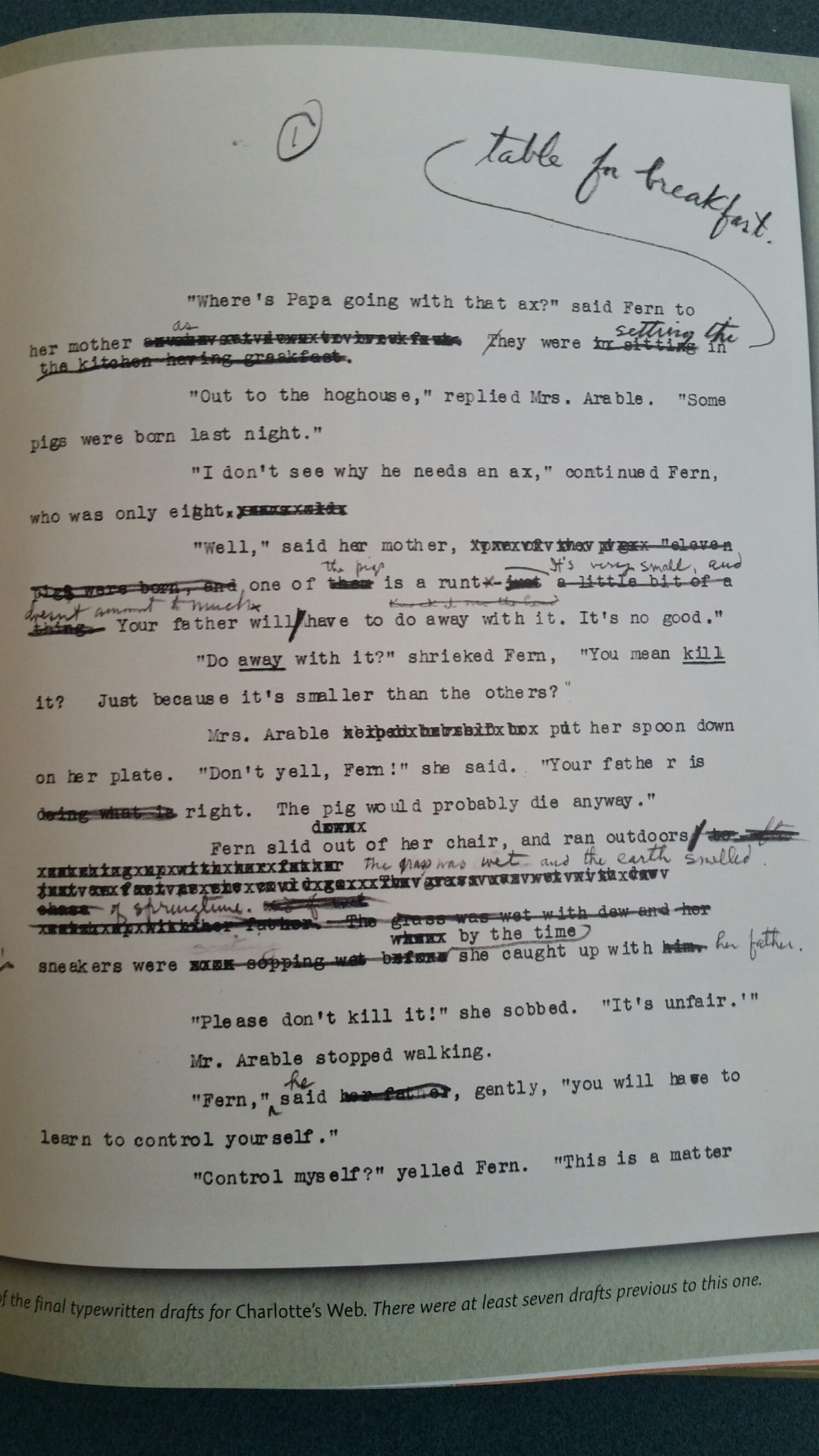

“Where’s Papa going with that ax?” said Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast.

It gets so much done with such economy: it speaks of danger, of domestic life and a rupture with domestic life, and of love. It asks the question that hangs over the entire book. It signals us that, while the novel's plot might appear to be about friendship, the stakes are actually very, very high.

One of my weaknesses as a writer is that I can’t continue on a project without having my opening sentence in place. “The pigs ate everything” is how my own novel, Pigs, opens. That sentence has been there since the first day I started working on it; in fact, it’s what made me want to sit down and start work on it in the first place. Pigs went through multiple drafts (seventeen, in fact), but, except for a terrible, terrible tenth draft, that first line has remained consistent.

In getting ready for the Charlotte’s Web talk, I came across a copy of the first page of one of White’s drafts. As it turns out, White is not a writer who needs a first line in place to get going.

Looking at the manuscript page, I’ve come to think of White as a writer who carved, who created texture and then cut away to find the essential underneath. I’ve started work recently on a new novel and, seeing White’s draft, I feel a great sense of freedom to write it rough and to trust that beneath that roughness there will be something to cut down to, something that, a few drafts from now, I’ll discover as the key that unlocks the beautiful thing I have to trust is there. I think I have a pretty good first line to work with, but this time around I'm going to give myself the space to recognize that maybe something as near perfect as his is hidden in the draft somewhere, waiting for me to find.

I’d love to hear on my Facebook page if you can suggest any opening sentences from books you love that resonate for you the way White's does for me.